Long-delayed legislation is more than doubling the CalSTRS rates paid by school districts and the state. But even if the all-important pension fund investment earnings are on target, the huge CalSTRS debt is expected to continue to grow for another decade.

The Legislature left CalSTRS rates frozen for nearly three decades before enacting the massive rate increase three years ago. Now there are signs that the Legislature may be assuming more responsibility for CalSTRS funding.

The 2014 legislation freezes rates paid by school districts at 20.5 percent of pay, after they more than double to 19.1 percent by the end of this decade. But under new power given the CalSTRS board, the state rate can continue to increase up to 0.5 percent of pay each year.

Last week, an update on California State Teachers Retirement System funding from the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office said prior to the legislation the “responsibility for funding CalSTRS was not defined in law.”

CalSTRS has been unusual in at least two ways: powerless to raise employer rates, and receiving state funding. Most California public pension systems, including CalPERS, can raise employer rates and only get annual payments from employers and employees, not the state.

The Analyst’s report said the CalSTRS funding legislation gives the state a larger share of the debt or “unfunded liabilities” that increased to $97 billion in the fiscal year ending last June, up $21 billion from $76 billion the previous year.

Most of the debt increase was due to the CalSTRS decision to lower its investment earnings forecast (used to discount future pension obligations) from an annual average of 7.5 percent to 7 percent and to increase the expected average life span of retirees.

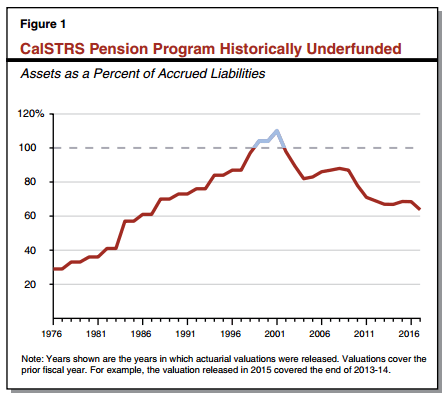

Actuaries said CalSTRS, only 64 percent funded last June, is still on track to reach 100 percent funding by 2046. Whether CalSTRS remains on the path to full funding, said the Analyst, will largely depend on whether the state pays enough under the new plan.

“If the Legislature wants to increase the likelihood that the funding plan succeeds in achieving this goal, it probably needs to ramp up state contributions faster,” said the Analyst’s report.

The Analyst suggested raising the 0.5 percent of pay cap on state contributions, using some of the Proposition 2 “rainy day” debt payment fund approved by voters in 2014, or combining the two.

Last month, the CalSTRS board was told that a Senate budget subcommittee asked for an analysis of the effect on CalSTRS funding from a “capital infusion,” as of next January, of $250 million, $500 million, and $1 billion.

Robin Madsen, CalSTRS chief finance officer, told the board her understanding is “this would be like a curtailment of principal in terms of the unfunded actuarial liability and not have an impact on current contribution rates from either the state or the employer community.”

A new risk report given to the CalSTRS board last November explained that when payments into the pension fund are not large enough to cover the interest on the unfunded liability, the unfunded liability will continue to grow.

Actuaries call it “negative amortization.” About $4 billion of the $21 billion increase in the CalSTRS unfunded liability last fiscal year is attributed to contributions that were not large enough to cover the interest on the debt, then 7.5 percent.

In the November risk report the debt was expected (assuming investment earnings are on target and no other changes) to continue to grow until 2027. Actuaries gave the CalSTRS board an annual valuation last month reflecting the new 7 percent earnings forecast.

“As was reported last November, the UAO (unfunded actuarial obligation) is expected to continue to grow for the next decade and then start declining,” the actuaries said in their report.

Not having unpaid interest add to pension debt is one benefit of trying to keep pensions fully funded. As mentioned in a previous post, the New York State Teachers Retirement System, 104 percent funded last year, quickly raised rates after large investment losses.

Not passing large debt to future generations is another benefit of fully funded pensions. As mentioned in another post, “intergenerational equity” is why some actuarial theorists advocate investing pension funds in risk-free government bonds, despite low yields.

“A central tenet of public finance holds that expenses should be paid for during the year in which they are incurred,” the Analyst’s report said last week. “Applied to pension programs, this principle means that benefits should be funded during employees’ working careers.”

Having a cushion against large stock market losses during economic downturns is yet another benefit of full funding. Despite a lengthy bull market, CalSTRS was only 64 percent funded at the end of last fiscal year.

“I would say if you get below 50 percent, it’s really hard to recover,” Nick Collier, a Milliman actuary, told the CalSTRS board last month. “Maybe the number is a little bit higher than that. But I wouldn’t go below 50 percent.”

Like the larger California Public Employees Retirement System, CalSTRS has not recovered from huge investment losses a decade ago during the financial crisis and stock market crash.

The value of its portfolio, tilted toward stocks and other risky but higher-yielding investments, dropped from $180 billion in October 2007 to $112 billion in March 2009. At the board meeting early last month, CalSTRS briefly celebrated investments reaching $200 billion.

Meanwhile, as mentioned in yet another post, the actuarial report given to the board last month showed that while the value of CalSTRS investments grew by nearly three-quarters from 2000 to 2016, the actuarial obligations to pay future pensions nearly tripled.

CalSTRS faces head winds in the move toward full funding. Less favorable economic conditions, in the view of experts, along with longer expected retiree life spans were the main reason for lowering the earnings forecast from 7.5 to 7 percent.

The risk report last November, which described negative amortization, also said CalSTRS is a maturing pension system. The active-retired worker ratio, nearly 6 to 1 in 1971, dropped to 1.5 to 1 in 2015.

Growing negative cash flow, which began in 1999, was about $5 billion last fiscal year, when pension payments totaled $13 billion and employer-employee and state contributions $8 billion. The gap has to be filled by pension funds, reducing earnings.

Larger rate increases are needed to replace investment losses. When the payroll and the pension fund were about equal in 1975, a loss of 10 percent below the investment target could be replaced by a 0.5 percent of pay rate increase over 30 years.

Now when the CalSTRS investment fund is about six times larger than the total member payroll, replacing a 10 percent loss would require a rate increase of about 3 percent of pay over 30 years.

The funding legislation in 2014 authorized CalSTRS to raise state rates, currently 8.8 percent of pay, by up to 0.5 percent of pay a year, reaching a maximum of 23.8 percent of pay before the legislation expires in 2046.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com. Posted 8 May 17