Legislation in 2014 to keep CalSTRS from running out of money in 30 years put a big burden on school districts. State funding rebounding from recession cuts helped schools absorb higher pension costs, spread over seven years to avoid budget shocks and allow time to plan.

But now there is worry. Pension costs are scheduled to grow for two more years as funding levels off. Reserves needed for the next economic downturn are depleting. School funding has an alarming history of sharp drops when a slowdown turns into recession.

Many schools are losing enrollment and per-pupil funding. Costs are rising for health, special education, transportation, utilities, and other services. And teachers, hit by soaring housing costs in urban areas, are pushing for higher pay with several well-publicized strikes.

CalSTRS pension funding never recovered from a huge investment loss a decade ago, leaving it like schools ill-prepared for the next downturn. Two years ago, the latest calculation, CalSTRS only had 63 percent of the projected assets needed to pay future pensions.

The good news for CalSTRS is the 2014 funding plan remains on track to reach 100 percent around 2046, even if investments falter for a few years. The portfolio was valued at $228 billion at the end of last month. The debt or unfunded liability has been about $107 billion.

Critics say the current CalSTRS earnings forecast, 7 percent a year, is too optimistic. In a recent reply, CalSTRS said its earnings forecast is a little below the public pension plan average, 7.2 percent, and a little above the corporate pension plan average, 6.8 percent.

CalPERS also has a 7 percent earnings forecast. A Wilshire forecast two years ago, sometimes cited by critics, expected the current CalPERS portfolio to earn 6.2 percent during the next decade. This year Wilshire raised its forecast to 6.75 percent.

Unlike CalPERS and other public pension systems, CalSTRS gets part of its funding from the state and has lacked the power to raise employer rates, needing legislation instead. Despite years of pleading by CalSTRS, the Legislature waited until 2014 to raise rates.

A CalSTRS analysis found that if the 2014 funding plan had been enacted shortly after the huge investment loss in 2008, the current funding level would be not 63 percent but 70 percent, similar to the CalPERS funding level.

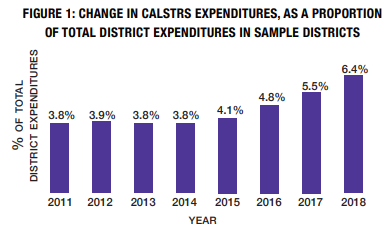

The funding plan more than doubled school district rates, pushing them from 8.25 percent of pay to 19.1 percent of pay over seven years. Rates for most teachers went from 8 percent of pay to 10.25 percent.

For the first time CalSTRS was given power to raise rates, tightly limited. After school district rates top out at 19.1 percent next year, the CalSTRS board can raise employer rates up to 1 percent a year, but no higher than 20.25 percent of pay.

Much more money can come from the new power to raise state rates, already up from a base of 4.5 percent of pay to 9.8 percent this fiscal year. The CalSTRS board can raise the state rate up to 0.5 percent of pay each year until the funding plan expires in 2046.

At a meeting in January, some CalSTRS board members were skeptical about reports of the impact of rising pension rates on school budgets. The staff was urged to think about giving the public a more balanced view of how the rate increase was planned and shared.

The CalSTRS board approved a proposal by the chair, Dana Dillon, for a staff report on the impact of the pension rate increases on school districts that is “more data driven than anecdotal.”

Pivot Learning, a nonprofit school consultant in Oakland, issued a report this month on rising school pension costs. It’s based on ten years of budget data for 98 school districts, a survey of school board presidents in 115 districts, and interviews and focus groups with others.

In a third of the districts, “The Big Squeeze” found rising pension costs increased class sizes and cut enrichment programs such as art, music and after-school activities. While pension costs rose, the share of school district budgets spent on teacher pay declined 5 percent.

After the recession average teacher salaries increased from $67,900 in 2011 to roughly $79,100 in 2017, up 17 percent. If not for the rapid rise in pension costs, said the report, the increase in teacher salaries likely would have been larger.

“California’s pension squeeze is exacerbating the inequity in public schools by forcing school districts to decrease services to our neediest students,” said the report.

To pay growing pension costs 23 percent of the districts are using Local Control Funding Formula supplemental and concentration grants that “are supposed to be used to increase and improve services for low-income students, English learners and foster youth.”

All respondents to the survey conducted with the California School Boards Association said their pension costs increased during the last three years, a time when 91 percent said health care costs also were increasing.

“A stunning 57 percent indicated that they expect these costs to result in deficit spending in fiscal 2018-19,” said the report.

A Legislative Analyst’s Office report last month said the annual school payment to CalSTRS in fiscal 2013-14, the year before the seven-year increase began, was 8.25 percent of pay or $2.3 billion.

When the last annual payment is made in fiscal 2020-21, the scheduled rate is 19.1 percent of pay and the analyst’s report estimated that the annual payment will be about $6.8 billion, nearly tripling over the seven-year period.

School payments to the California Public Employees Retirement System for non-teaching employees are smaller than the California State Teachers Retirement System payments, but also may roughly triple over the seven-year period.

The new school rate set by the CalPERS board this month (20.7 percent of pay) requires a $2.95 billion payment in the new fiscal year beginning July 1, up $480 million from the current year. The payment in fiscal 2013-14 was $1.17 billion.

No dollar amount was available from CalPERS last week for the payment expected in the fiscal year beginning July 1 next year. But the rate for fiscal 2020-21 is estimated to be 23.6 percent of pay, more than double the 11.4 percent rate in fiscal 2013-14.

Meanwhile, school funding from the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee has grown nearly $22 billion (37 percent) from fiscal 2013-14 through the current fiscal year, said the analyst’s report.

Gov. Newsom’s proposed budget for the new fiscal year has a 3.8 percent increase in school funding. Adjusted for inflation, said the analyst, per-pupil school funding is at an all-time high.

Responding to school pleas for rate relief, Newsom proposed spending $350 million in each of the next two fiscal years to lower the last two scheduled CalSTRS rate increases by 1 per cent, dropping to 17.1 percent of pay next fiscal year and 18.1 percent in 2020-21.

The Legislative Analyst’s report said the Legislature should consider setting aside the $700 million for school district rate relief to reduce the need for CalSTRS rate increases during a future downturn.

“Though districts view rising pension costs as difficult to manage today, these difficulties could become much more pronounced during a downturn,” said the analyst’s report.

If school funding gets even tighter in the future, the Legislature could look at the unique and never-analyzed CalSTRS inflation protection program, which has a $9.8 billion surplus and has only been spending around $165 million a year for three decades. (See details here.)

Newsom also proposed spending $2.3 billion to pay down the school district share of the CalSTRS debt over four years and a one-time $3 billion payment on the state share of the CalPERS debt. Each payment is expected to save more than $7 billion over three decades.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com. Posted 29 April 2019

April 29, 2019 at 6:24 am

This situation is not unique to education or to California or even to state and local government. The wages and salaries of state and local government workers are at the lowest level of the past nearly 50 years.

And discretionary federal spending has shrunk away as well. All to pay for what a generation promised itself but was unwilling to pay for.

The life expectancy of later-born generations is falling. This goes way beyond $.

April 29, 2019 at 7:35 am

How about looking into how STRS and Lands Commission are doing with the School Lands issue.

April 29, 2019 at 9:29 am

“The wages and salaries of state and local workers are at the lowest level of the past nearly 50 years.” Is your nose growing?

The facts are just the opposite. And here in Pacific Grove, for each $125,000 of police salary, the city must pay another $125,000 for pension costs, including amortization of pension debt: Did you count that sum as salary? Why not, it is paid in exchange for salaried work. Of course it is salary, but part of the scam is to ignore reality.

Ed writes about the Ca. pension crime as if it was other than a salary and pension scam. You agree. We get that, but non-govt. workers in the private sector, except for the very rich, cannot afford housing and health care, but legislators don’t care. They have theirs, so the scam continues.

April 29, 2019 at 11:54 am

At the lowest level as a percent of the personal income of all U.S. residents.

Pensions, other retiree benefits and debts are sucking up all the money.

Read the post and download the spreadsheet. There is data on every state. The charts show the trend is the same everywhere.

May 2, 2019 at 4:24 pm

Compensation = Salary plus Benefits. Salaries have not increased as much as teachers and other school employees have hoped (and need to rise given student loan debt and high rents), but securing CalSTRS is essential for their future, particularly since CalSTRS members don’t receive Social Security. School employees also have good health benefits, and increased premium costs have contributed to the rise in the non-salary part of total compensation. California is a wealthy and expensive state but is stingy in funding K-12 education. Education isn’t the gig economy; it costs money to employ a college-educated workforce.