A new report shows a third of local governments in CalPERS will have police and firefighter employer rates next fiscal year that are at least 50 percent of pay, a level that a former CalPERS chief actuary believed a decade ago would be “unsustainable.”

At the high end, the number of local governments with rates of 70 percent of pay or more (all of them cities except for one special district) will increase from 15 this fiscal year to 24 in the new fiscal year beginning July 1.

The average “safety” or police and firefighter employer rate will increase 4.75 percent next fiscal year, going from 44.23 percent of pay now to 48.98 percent next July, said the annual CalPERS Funding Levels and Risks Report given to the board last week.

The average safety rate is projected to continue to grow, up from 44.23 percent of pay this year to 55 percent of pay in 2024. Rates for at least one large city, Santa Ana, are expected to increase from 72.6 percent of pay this year to 100 percent of pay in 2024.

“The greatest risk to the system continues to be the ability of employers to make their required contributions,” said the new report.

With a few exceptions, employers are making required monthly payments to CalPERS on time. But the ability to absorb high rates varies widely among the 1,578 “public agencies” in the system: cities, counties, and special districts.

The report said there is evidence some public agencies are “under significant strain,” citing collection activities and requests for longer debt-payment periods and for information about leaving CalPERS.

After the CalPERS investment fund plunged from $260 billion to $160 billion in the financial crisis and stock market crash a decade ago, the CalPERS chief actuary then, Ron Seeling, issued a warning at a Retirement Journal seminar in August 2009.

Seeling said his personal belief was that CalPERS was facing “unsustainable pension costs of between 25 percent of pay for a miscellaneous (nonsafety) plan and 40 to 50 percent of pay for a safety plan . . . We’ve got to find some other solutions.”

The CalPERS investment fund, doubling since the crash, was $347 billion last week. But pension debt or “unfunded liability” grew faster, driven by investment losses, longer lifespans, and a drop in the earnings forecast used to discount debt to 7 percent.

Now the CalPERS systemwide average funding level, 100 percent before the crash, is only 71 percent of the projected assets needed to pay the future pension costs of a growing number of retirees.

The low funding level, well below the traditional 80 percent minimum, is slim protection against a market crash or slump that drops funding below 50 percent, a red line experts say makes recovery to 100 percent difficult if not impractical.

CalPERS seems to have few workable options to improve its funding level, other than to continue to assume long-term investments will solve the problem, even though critics say a 7 percent earnings forecast is too optimistic.

Another employer rate increase, as previous hikes are straining local budgets, would be difficult. Higher employee rates, now about 10 to 15 percent of pay for safety workers, must be bargained with unions and may have limits.

Gov. Brown’s cost-cutting pension reform in 2013 for new hires will take years to have a modest impact. CalPERS expects the reform to save $29 billion to $38 billion over 30 years, a small reduction in a $138.6 billion unfunded liability as of June 30, 2016.

A major reform proposed by the bipartisan watchdog Little Hoover Commission in 2011, going beyond new hires, would allow cuts in the pensions earned in the future by workers hired before the Brown reform, while protecting amounts already earned.

But under a series of state court decisions known as the “California rule,” the pension ofered at hire becomes a vested right that can’t be cut unless offset by a comparable new benefit, erasing the savings.

The state Supreme Court has scheduled a hearing Dec. 5 on a case some think may modify the California rule. After a 14-month delay, Brown filled a vacant Supreme Court seat last week by appointing his legal advisor, Joshua Groban.

Brown said last January he has a “hunch” the courts will modify the “California rule,” so “when the next recession comes around the governors will have the option of considering pension cutbacks for the first time.”

Among the number of local governments that have raised taxes to help cover the growing cost of CalPERS pensions, the small city of Oroville has been one of the most forthright, warning that the alternative could be bankruptcy.

As cities lined up at a CalPERS board meeting last fall to ask for relief from rising pension costs that are forcing cuts in staff, pay, and services, the Oroville finance director, Ruth Wright, told the board, “We have been saying the bankruptcy word.”

Wright said the city had recently negotiated a 10 percent pay cut with police, the workforce had been cut by a third two years earlier to help balance the city budget, and the “cash flow” would be gone in three or four years.

This month Oroville voters approved a 1-cent sales tax increase, after rejecting a similar proposal two years ago, as well as a 10 percent tax on marijuana businesses, which have not yet opened pending approval by the city.

Previous bankruptcies have shown that cities may be unlikely to cut pensions, particularly for vital police and firefighter services, even if the California rule is modified by the state Supreme Court.

Officials in Stockton, a city with a high crime rate, said from the outset of bankruptcy they would not cut pensions, needed to be competitive in the job market. But the Stockton case did produce a federal court ruling that CalPERS pensions can be cut in bankruptcy.

San Bernardino had the strongest case for cutting pensions. The city filed an emergency bankruptcy in 2012, somehow surprised to learn that it would soon be unable to meet payroll, and then skipped contract-required monthly payments to CalPERS for a year.

“The city concluded that rejection of the CalPERS contract would lead to an exodus of city employees and impair the city’s future recruitment of new employees due to the noncompetitive compensation package it would offer new hires,” San Bernardino said in a court filing two years ago, echoing Stockton’s position.

“This would be a particularly acute problem in law enforcement where retention and recruitment of police officers is already a serious issue in California, and where a defined benefit pension program is virtually a universal benefit.”

Vallejo officials said consideration of pension cuts was deterred by a CalPERS threat of a costly legal battle. Like San Bernardino, Vallejo still has to close recurring budget gaps and faces high CalPERS safety rates next year: San Bernardino 82.6 percent of pay, Vallejo 78 percent.

Stockton, with a CalPERS rate of 59.7 percent of pay, looks like success to some. A national nonprofit organization, Truth in Accounting, ranked Stockton No. 2 among the nation’s most populous 75 cities in terms of fiscal health, based on debt or surplus per capita.

“According to its research, Truth in Accounting found that Stockton has a surplus of $3,000 per resident, and gave the city a “B” on its grading scale,” the Stockton Record newspaper reported last May.

The new risks report shows that local governments have a wide range of CalPERS pension costs. Actuaries attribute much of the difference to varying payrolls and other factors, some of them large such as a police or firefighter unit transferring to another system.

CalPERS encourages employers, if able, to make additional contributions to lower their risk of lower funding and higher future contributions. Last year 195 employers contributed a total of $538 million, up from 185 employers and $228 million in the previous fiscal year.

A generous police and firefighter pension formula, geared toward early retirement from strenuous jobs, has a much higher cost than the “miscellanous” pensions for nonsafety employees.

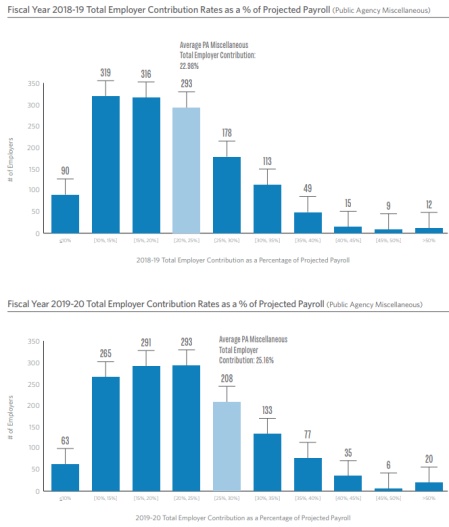

But the new risks report shows that the average CalPERS miscellaneous rate will reach the level the former chief actuary believed would be unsustainable: 25.16 percent of pay next fiscal year, up from 22.98 percent this year.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com. Posted 19 Nov 18

Share this:

November 19, 2018 at 10:03 am

Actually, The Ca. Rule only comes into play “if” the pension was granted with the legislative intent to make it vested(like in the Long Beach cases where the court found that the City Charter had granted a vested right) In the upcoming “air time” case the court has raised the issue of whether it had been authorized as a “vested right,” if not, it could be eliminated. In the Amy Monahan 2010 law review article, professor Monahan described the California Rule to mean that in those states that followed it, vested pension rights could not be diminished “for work not yet performed.” In most states, legislatures may reduce pensions for work not yet performed. The “new” definition of the Ca. Rule is a product of comments made on P.Tsunami and as three appellate courts have now said, vested pension rights may be reduced w/o off-set if the facts show it is necessary to protect the integrity of the plan(like PEPRA). Those cases are to be heard by the supreme court in the near future.

November 19, 2018 at 10:25 am

All this is because CalPERS claimed that the stock market would pay for retroactive pension increases of 50%. In addition, when they suggested to their agencies they adopt the new formulas they gave the agencies 3 ways to value the assets in their plan. In Pacific Grove the cost using the current value of assets was an additional 25% of payroll and with the 3rd alternative for valuing assets at 110% of market value the cost of the increase would be only 2% of payroll, which is the number the city manager gave to the City Council. So they approved it.

Section 7507 of the government code required taxpayers to be given the future annual cost of the increase at a meeting 2 weeks ahead of its adoption, but that never happened in any city in the state because CalPERS never mentioned it to the cities in their instructions for how to increase pensions. So all these pension increase violated state law. But who is going to enforce the law?

At the least local papers and you Ed should be reporting on how these laws were violated.

Here is a place for you to start Ed: http://www.newsonoma.org

November 19, 2018 at 12:26 pm

Ken is right on. In Pacific Grove, by allowing it to value assets at 110% of market it was worse than one might think. In 2002, CaLPERS had had about a 20% loss in 2001 from the tech crash and the pension payment forgiveness program, but PG used the 2000 market value which was 20% higher than market in 2002.

CalPERS represented that the annual cost for 3%@50 was $50,500, but in fact it was $880,000. By 2004, Pacific Grove could not make the payment and had to restructure with CaLPERS at an additional cost. All of the unions certified to CaLPERS that if it did not restructure, PG was cash insolvent.

In 2006, Pacific Grove issued $38M in pension bonds and gave the police a spiked raise of 30%. You can’t make this stuff up!

November 19, 2018 at 12:36 pm

CalPERS has many problems. The airtime issue is a relatively minor one if they calculate the cost of the airtime properly – the employee pays for it if they do. Another problem is brought to mind because of an interesting comment in a recent Sonoma County (separate, not PERS system) newsletter: social investing. SCERA points out that their purpose – their ONLY purpose – is to guarantee employee pensions. Not to invest for social purposes. PERS seems to be more of a politico-social investing group. SCERA’s about 87% funded (2017 data), and that includes some safety (Sheriff) pensions. PERS is nowhere near that. Could the social investing aspect of PERS be contributing substantially to the shortfall?

November 19, 2018 at 12:39 pm

The “traditional 80 percent minimum” funding level is only appropriate when markets are in a financial trough. Pension obligations should be fully-funded on average, which means at market peaks they will be over-funded, something that will likely go away as markets fluctuate without politicians intervening to treat it as a windfall.

November 19, 2018 at 2:38 pm

So what happens to promised pensions in a place like Paradise? Was the city, or special districts, a part of PERS? What if a city just vanishes?

November 19, 2018 at 2:43 pm

Every city council, special district board, etc. should have a mandated class on pensions. Most don’t even know what 2% at 55 means. Yet, other politically correct classes are mandated. Not understanding pensions does a lot more damage to government entities.

November 19, 2018 at 2:58 pm

There was never a pension increase of 50 percent, retroactive or otherwise, except for those few officers who actually retired at age 50.

The change was from a nominal 2%@50 to a nominal 3%@50. The 2%@50 formula, however, graduated to 2.7%@55. One who retired at 55 with 30 years service under the old formula would receive 81 percent of final salary vs 90 percent under the new formula.

November 19, 2018 at 4:04 pm

When Pacific Grove issued pension bonds in 2006, just over 50% of the deficit was from 2%@55(Misc. employees), the rest from 2%@50 and the creation of 3%@50. The system fails at all of the referenced levels.

At that time there were many more Misc. employees than safety, but now safety out numbers Misc.. Police and Fire unions are the “Bosses” of the pension scam.

November 19, 2018 at 5:02 pm

June you bring up a good point. The city has no money and no income stream. They were deep in debt with a $19 million pension liability at a 7.65% return assumption, $28.5 million at 6.65% and if they want to buy themselves out of CalPERS, which they will have to do the assumed rate is 3% and the net liability is $78 million according to their on line CalPERS actuarial report and their financial statements.

They also have $10 million in pension bond debt and had $39 million in capital assets that are all gone now.

Basically, they only have $4 million in the bank and no sales or property tax income.

So they need the federal government and state government bail-out to rebuilt.

Also, the residents will get their insured value of their structure which they will need to pay off their mortgage. They will be left with a worthless lot if there is no bailout. So they might not even have the money they need to buy something else. Renters lost everything. It is so sad.

November 19, 2018 at 5:06 pm

Stephen why do you keep posting incorrect information? If someone made $100,000 when they retired and worked 30 years in safety and were over the age of 50 their pension would be 60% of their salary under the old 2% at 50 formula and $90,00 under 3% at 50. How is that not a 50% increase?

November 19, 2018 at 8:09 pm

Before SB400, CHP and many other safety pensions were 2%@50…

Page 30…

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://www.calpers.ca.gov/docs/forms-publications/state-safety-benefits.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjN28C8hOLeAhXsRd8KHZNXBJ0QFjAAegQIARAB&usg=AOvVaw1jOP7WqSJC-FTk8WLcqgGX

2%@50 is the nominal formula. It gradually increases to 2.7%@55.

” If someone made $100,000 when they retired and worked 30 years in safety and were over the age of 50 their pension would be 60% of their salary under the old 2% at 50 formula…”

Correction… if they were EXACTLY 50 with 30 years service, their pension would be 60% of salary.

If they were 51 with 30 years, the pension would be 64.20%

At 52 with 30 years, it would be 68.40%

And so forth (page 31)… up to age 55 with 30 years, yielding 81%.

Last I heard, average CHP retirement age was 54. I haven’t read what the average length of service is. Keep in mind, the average age of CHP Cadets is mid to late twenties.

The newest (2013) formula is actually slightly less generous than the pre SB400 formula, as the graduated formula reaches 2.7% at 57, instead of 55 (2.7%@57, page 44).

November 20, 2018 at 9:35 am

It’s amazing that “entitlement” to those promised DEFINED benefits, will drive the so called “entitled” to put the costs of those entitlements onto their kids!

State and local workers are promised generous DEFINED BENEFIT PENSION PROGRAMS that few private sector companies offer any longer because they are unaffordable. Making matters worse, thanks to complicit politicians, the state and local governments have failed to adequately fund these overly generous DEFINED benefit pensions. The huge unfunded pension liability debt crisis is the inevitable result that younger generations, unable to vote today, that will bear the costs.

Fully funding these pensions is unfair to current hard working taxpayers, so the “consensus” of the courts and current taxpayers is to defer the responsibilities for paying for these overly-generous “Defined retirement benefit” pension programs to younger generations, for them to pay higher taxes and work later into their lives to pay for the promises of previous generations, to subsidize older Americans.

It’s frustrating and appalling that the “courts” are actually saying that future generations will continue to be legally responsible for DEFINED BENEFIT PENSION PROGRAMS established by previous generations! Are the courts really supporting taxation on younger generations without representation?

November 20, 2018 at 3:10 pm

rstein171 – The vast majority of kids paying for these retirements won’t be the kids of beneficiaries. The judges who decide what’s right are members of the pension system.

Click to access jrs-ii-benefits.pdf

November 20, 2018 at 3:44 pm

June Vanwingerden- Citizens too need to understand the pensions they are liable for as taxpayers. Unfortunately the journalism on pensions is quite bad. Ed Mendel is an exception, just as he was when he was reporting on energy deregulation is this state.

One of the great distortions I’ve seen from reporters is the common portrayal of unfunded liabilities as something in the future to pay rather as the net present value of a debt that bears a vastly higher rate of interest than other government debt. It is like a loan at 7-7.5% interest and it required no voter approval.

Another thing is that citizens without such generous defined-benefit pensions should understand what it would take to buy the equivalent annuity for themselves on the market. I think that’s a valuable perspective to have.

Finally, everyone, both regular citizens and government employees, should understand any system that doesn’t align benefits with the way pension funds earn implicitly transfers the contributions of some to others, excluding the insurance redistribution based upon the luck of longevity. Those who are fortunate enough to have bumps in their earning late in their careers get windfalls. It also leads to rational jurisdiction shopping for better wages within the system. Changing the final salary calculation amount can pay pension windfalls for decades.