As CalSTRS rates are more than doubling, squeezing school budgets, an inflation-protection account that keeps teacher pensions from dropping below 85 percent of their original purchasing power has a large and growing excess of funding, $5.6 billion last year.

Gov. Brown put a new focus on quickly paying down pension debt this year with a $6 billion extra payment to CalPERS for state workers, estimated to save $11 billion over two decades if all goes as planned.

The governor’s finance department, which is working on a new state budget to be proposed in January, declined to comment last week on whether using the inflation-protection reserve to pay down CalSTRS debt is being considered.

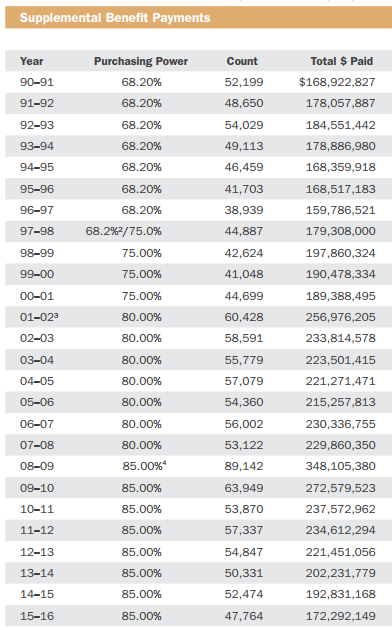

The annual state payment to the Supplemental Benefit Maintenance Account far exceeds inflation-protection payments to retirees. Inflation has been low, and the unusual structure of the account evolved over time, apparently with no analysis of cost efficiency.

Payments to retirees are little changed in 25 years. In fiscal year 1990-91 the annual payment to 52,199 retirees was $169 million. In fiscal year 2015-16, the latest data available, the payment to 47,764 retirees was $172 million.

But each year the state is required by law to contribute 2.5 percent of teacher pay (minus $72 million) to the account. The payment this fiscal year is $695 million, up from $649 million last year and $607 million in fiscal 2015-16.

When the state withheld a $500 million payment to the account in 2003 to help balance the state budget, CalSTRS filed a lawsuit. The courts ruled that the failure to pay was an unconstitutional contract violation and ordered repayment with interest.

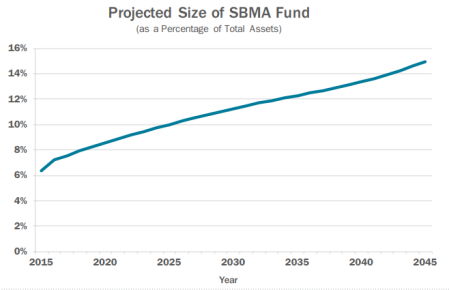

Not surprisingly, the result of the lopsided flow of money into and out of the account is a rapidly growing reserve. The latest available total for the reserve is $12.8 billion last fiscal year, more than doubling from $5.3 billion in 2008.

CalPERS has a similar program that maintains 75 percent of original purchasing power for state workers, 80 percent for local government retirees. But it’s paid by the usual employer-employee contributions and investment earnings, not maintaining a huge reserve.

Whether CalSTRS could adopt a CalPERS-like program and make significant savings, while easing any retiree anxiety about losing inflation protection, apparently has never been studied.

The current goal of the unusual CalSTRS method of funding inflation protection is maintaining a reserve large enough to keep pensions at 85 percent of their original purchasing power through 2089, if inflation averages 3 percent.

Inflation-protection payments are said to be a vested right of CalSTRS members, but only to the extent they can be paid by the account. CalSTRS actions are based on the arguable assumption that lawmakers won’t put more money into the account if there is a shortfall.

Last year a CalSTRS report said the large account reserve and projected future state payments are more than enough to make the inflation payments until 2089, if inflation is 3 percent.

“The result is $5.6 billion in resources in excess of the amount projected needed to maintain 85 percent purchasing power through June 30, 2089, primarily from future contributions,” said the report.

If inflation stays at 3 percent or less, said the report, the 85 percent purchasing power can be “sustained indefinitely.” But the report also said the account “will be depleted by 2080 if inflation increases to 3.5 percent, and by 2045 if inflation increases to 4 percent annually.”

In June last year the CalSTRS board looked at two options for using the $5.6 billion excess to increase pensions before adopting a staff recommendation to make no change, protecting the ability to keep purchasing power at 85 percent in the long run.

Not only could inflation go above 3 percent, but the CalSTRS earnings forecast, dropped from 7.5 to 7 percent in February, could be lowered again. The inflation account reserve is credited with the forecast earnings, even if returns are above or below the target.

One of the options for using the excess funds would have given a pension increase to members who retired before 1999, ranging from 1 to 6 percent depending on how long they had been retired. A similar increase was given CalSTRS retirees by legislation in 2000.

A pension reform that took effect four years ago includes a ban on retroactive pension increases. The CalSTRS staff report said legislation would be needed to override the ban if the board chose to increase retiree pensions.

The other option would have raised the purchasing power support from 85 percent of the original pension to 91 percent. An analysis using several different inflation and earnings forecasts showed that 91 percent could be sustained through 2089 by the $5.6 billion excess.

Several speakers associated with retiree groups passionately urged the CalSTRS board to find a way to raise the pensions of long-time retirees, who received little benefit from benefit increases for active workers around 2000 when the main pension fund had a brief surplus.

Elderly retirees, many of them single women with small pensions, were said to be struggling to pay rising utility and health costs. CalSTRS members don’t receive Social Security. Many have no retiree health benefits, unlike state workers and other government employees.

“I think you need to do something,” Pat Geyer told the board. “Because the other thing thing that is going to happen if you don’t use it, you lose it. I’m really concerned that someone else will find a good reason to spend this money, and the retirees will be left without.”

CalSTRS pensions lose purchasing power when inflation rises because the annual cost-of-living adjustment is a fixed amount, 2 percent of the original pension. The CalPERS cost-of-living adjustment compounds, ranging from 2 to 5 percent depending on union bargaining.

The CalSTRS inflation account was created in 1989 by legislation that phased in the state contribution of 2.5 percent of pay to restore 68 percent of purchasing power. As the reserve grew, support increased in several steps to 85 percent in 2008. (see previous post)

One of the reasons for the unusual inflation account is that CalSTRS, in addition to receiving contributions from employers and employees, also receives contributions from the state, unlike CalPERS and most California public pension sysems.

And CalSTRS, unlike CalPERS, has lacked the power to raise employer contribution rates. When long-delayed legislation raised rates in 2014, the CalSTRS board received the power to raise state rates, now about 9 percent of pay, by up to 0.5 percent a year until 2046.

Rates paid by teachers before the pension reform in 2013 increased from 8 to 10.25 percent of pay. The rate paid by school districts are more than doubling, going from 8.25 percent of pay to 19.1 percent by 2020.

School district budgets are being squeezed by rising CalSTRS and CalPERS rates for non-teaching employees. At the CalPERS Educational Forum last month, one official said across the state about 80 percent of this year’s new school funding is going toward pension costs.

“There is a perception that there is new funding coming toward K-12, but there is not the realization when we do the math of how much is actually discretionary and available to go into the classroom once you factor in pension costs,” said Megan Reilly, Santa Clara County Office of Education chief business officer.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com. Posted 6 Nov 17

November 6, 2017 at 7:34 pm

The state made the extra payment to CaLPERS by raising the gas tax and car registration fees. Taxes are fungible, the state pays for outrageous salaries and pension by announcing tax increases for roads and transportation because the taxes for that purpose were/are spent on salaries, pensions and medical insurance. JMM

November 13, 2017 at 2:53 pm

Sometimes I feel like I’m the only commenter here who went to school in California and still knows my 90+ year old former grade school teachers who worked for 40+ years and have really pathetic pensions. CalSTRS is really not the problem, as many studies have shown. CalPERS is… with its astronomical pensions to 50-year-old retirees.

November 14, 2017 at 12:22 am

Got the runoff ballot from CalPERS in the mail today. It’s not a secret ballot. I tore it up and put into the recycle bin.