Former San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed and current Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed have more in common than their last names. Both have the same broad pension story. But last week, Atlanta had a very different ending.

With growing pension costs eating into their city budgets, the two men pushed through reforms that could require employees to pay more for their pensions — up to 16 percent of pay more in San Jose, up to 10 percent of pay more in Atlanta.

Both were accused of pension reforms that led to police flight, depleting the force and reducing public safety. The two mayors, both lawyers, said city laws (the charter in San Jose’s case) say that pensions can be changed.

But in both cities, the employees or unions filed lawsuits contending their pension benefits are “vested rights,” protected by contract law, that can only be reduced if offset by a comparable new benefit.

Two years ago a superior court judge ruled the San Jose employee contribution increase violated employee vested rights. The city dropped the appeal this year in a settlement of the lawsuits against Measure B, approved by 69 percent of voters in 2012.

Last week the Georgia Supreme Court ruled the Atlanta employee pension contribution increase, approved by the city council four years ago, did not violate the vested rights of employees.

“Today’s ruling allows one of the most comprehensive and effective examples of pension reform in the United States of America to move forward,” Atlanta Mayor Reed said in a statement.

“Thanks to pension reform, 30 years from now the city will have saved more than $500 million and a pension deficit that was once protected to be over $1.5 billion will be zero,” he said.

For employers trying to cut pension costs, getting employees to pay more for their pensions can be important but difficult.

When the debt or “unfunded liability” soars, as happened after huge pension investment fund losses during the recession, it’s the employer or taxpayers who must pay to close funding gaps, not employees.

Employee rates are usually set by labor bargaining. Increases, if any, are relatively small. Some of the biggest come when employers, who agreed in bargaining to pay the employee rate, end the “pension pickup” or “employer paid member contribution.”

An extreme example of how employers pay more than employees is the city of Vallejo. The rate paid by police and firefighters, 9 percent of pay in CalPERS reports, was little changed during a 3½-year bankruptcy that ended in November 2011.

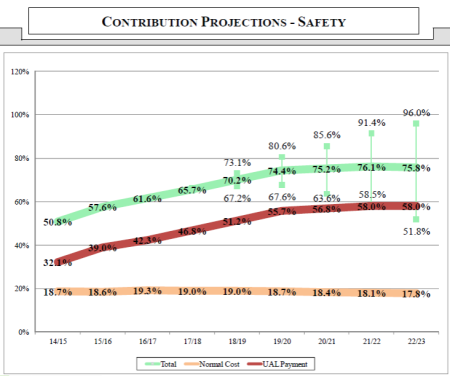

The employer rate, 28.3 percent of pay in 2009, is 57.6 percent of pay this year, and projected to be 72 percent in 2020. In the latest CalPERS report (June 30, 2013), the plan only had 64.6 percent of the projected assets needed to pay future pensions.

The powerful California Public Employees Retirement System, following projections by its actuaries, can raise employer rates. But CalPERS cannot raise the rates paid by employees.

A pension reform Gov. Brown pushed through the Legislature three years ago calls for a 50-50 split between the employer and employee of the “normal” cost, the pension earned during a year excluding the debt from previous years.

But the normal cost tends to be stable and a small part of total cost. In the Vallejo plan, the current normal cost is 18.6 percent of pay. The rate for unfunded debt from past years is twice that amount, 39 percent, bringing the total to 57.6 percent of pay.

The superior court ruling that blocked the San Jose employee contribution increase was based on what is often called the “California rule.”

A series of state court decisions, one in a 1955 Long Beach case, are widely believed to mean that the pension offered on the date of hire becomes a vested right, protected by contract law, that can only be cut if offset by a comparable new benefit.

The California rule was observed last year when the Legislature approved a rate increase for the California State Teachers Retirement System, which unlike CalPERS and other public pension systems has only tightly limited power to raise employer rates.

The teacher rate increase was limited to an amount said to be offset by a new benefit: An annual pension cost-of-living adjustment of 2 percent, a routine practice that could be suspended, was converted to a vested right.

Teachers and school districts had been paying nearly equal rates, 8 and 8.25 percent of pay, respectively. The teacher rate increase is a maximum of 2.25 percent of pay, increasing the rate for most from 8 percent of pay to 10.25 percent of pay.

The rate for school districts and other employers more than doubles, increasing in seven annual steps from 8.25 percent of pay to 19.1 percent of pay by 2020. A separate rate paid by the state, a total of 5.5 percent of pay, increases to 8.8 percent of pay.

Georgia is not among the dozen states that have adopted the California rule, according to Amy Monahan, a University of Minnesota law professor, in “Statutes as Contracts? The ‘California Rule’ and Its Impact on Public Pension Reform.”

The unanimous Georgia Supreme Court ruling cited several supporting rulings in Georgia courts while concluding that pension plans can be changed without violating vested rights, if change is clearly allowed by the pension contract.

The court said all three Atlanta pension plans contain language saying enrollment “shall constitute the irrevocable consent of the applicant to participate under the provisions of this act, as amended, or as may hereafter be amended.”

San Jose pointed to two city charter sections that say the city council has the power and the right to change, or repeal and replace, any of the city’s retirement plans or systems.

Superior Court Judge Patricia Lucas cited several California rule cases, including Allen v. City of Long Beach (1955): “Changes in a pension plan which result in disadvantage to employees should be accompanied by comparable new advantages.”

In the key part of her ruling on the rate increase, Lucas cited a state Supreme Court ruling, Legislature v. Eu (1991), and a footnote in a state appeals court ruling, Walsh v. Board of Administration (1992).

“Accordingly, this court concludes that a reservation of rights does not of itself preclude the creation of vested rights,” Lucas said.

Former San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed and former San Diego Councilman Carl DeMaio are leading a bipartisan group that is trying to put a pension reform initiative on the statewide November ballot next year.

After filing an initiative in June, the group refiled two initiatives last month, quickly amended. They want to avoid a ballot summary from Attorney General Kamala Harris suggesting the vested rights of current workers would be eliminated.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com. Posted 9 Nov 15

November 9, 2015 at 11:15 am

Judge Lucas, like Mr. Mendel were/are both wrong about the California rule. The Allen case, the 1955 case cited by judge Lucas and often by Mr. Mendel state the rights of an employee “if” it had a vested right. In Allen and previously in Kern v. City of Long Beach-a related case- the courts specifically found that a provision of the Long Beach Charter provided for a “vested” pension right. That in turn created a “contract right” as explained by Amy Monahan(“Statutes as Contracts”) and that contract right is protected by the contract clause of the Ca. Constitution. The constitution protects, but does not create vested contract rights.

The Ca. State Bar recently released a State Bar course entitled “Understanding ‘Vested’ and other Post Employment Vested Rights.”

It clearly explains what I have just said. To determine whether a vested right has been granted, the inquiry is whether the statute or contract that created the benefit was repealable, if a statute, or expired at the end of its term if a contract. If so, there was no vested right and the benefit may be modified by the legislative body.

There is a legal presumption that statutes and contracts do NOT create “vested” pension or other rights. The seminar was presented by the law firm of Libert Cassidy Whitmore, a large multi-office law firm with an emphasis in “Public Law” and approved by the “Continuing Education of The Bar” section of the Ca. State Bar. Ed-call them for a copy of the course materials.Or contact me at jmerton99@yahoo.com and I will provide you(or others) with a copy of the materials-I took the course which included a live video presentation You and Judge Lucas simply did not understand that everything that flowed in Allen was because it had a statute-the Charter- that made it clear that the Charter created a vested right. Amy Monahan agreed with what I have just said: her Article was entitled “Statutes as Contracts.” Why? Because just as the cases and the state bar seminar indicate, statutes are legally presumed repealable and there is a heavy burden to show that a statute was non-repealable; but it does happen. The seminar explains everything that I have just said.

As for judge Lucas, she ignored the primary test set forth in the seminar and the cases. In the San Jose case the issue was whether a Charter provision which authorized pensions, but also allowed granted pensions to be modified or even repealed granted a vested pension right(like the court found in Kern and Allen)? Not only did she not apply the test required by Kern, Allen, Monahan and the State Bar-what does the language intend-she failed to discuss the presumption that statutes and contracts do NOT create vested right. Clearly a statute like a Charter that provides for reduction of pension benefits in the same article that authorized pensions could Not create a vested pension right.

The Kern and Allen cases provided that even if a vested pension right was granted as in the two cases, if the pension system was failing-threatening the ability to pay promised pensions-pensions, reductions had been authorized by the Ca, supreme court without off setting comparable benefits. Cases exemplifiying this principle were cited in Kern; in Allen, the court made a point of stating that it was not a case where the pension system was failing: for that reason, reductions could not be made without off-setting benefits of comparable advantage. It is unimaginable that the Ca. supreme court that decided Kern and Allen would have found that even if a pension system was hopelessly broke, it cound never be fixed. That would have been tantamount to demanding that an Agency with a failed pension system must go broke(CaLPERS like).

November 9, 2015 at 5:16 pm

I have been asked to comment on Judge Lucas’ ruling that a court does not consider a reservation of rights in a Charter that grants the Council the right to set pensions.

The law for determining vested rights refers to the whole statute granting the pension benefit, both the power to grant pensions and the power to amend and repeal. Why? Because the inquiry was about the intent of the voters when they adopted the charter.

Judge Lucas made it a two part inquiry. Was there a benefit granted? Obviously yes. Was the power modifiable? Obviously Yes.

The judge found that a benefit was granted, but the law provided a way around the people’s intention that it was modifiable.

State salaries set by statute are vested unless the stature reserves the right to modify. In mid century, Ca. went from a part time to a full time legislature. In the Walsh case, the new statute providing pensions for full time legislators inadvertently substantially increased the pension for a part time legislator(Walsh). By a separate statute the legislature had enacted a reservation of rights statue to rectify errors made in the transition from part to full time. The court upheld the correction and Walsh had his pension reduced, but Lucas cited a footnote in the case that she claimed supported her decision to ignore the citizen’s legislative intent in providing a right to modify and repeal pensions. She did not discuss the fact that the right to modify was in the same charter provision as the right to grant a benefit. Very important to determine intent.

In Eu, a subsequent legislature dominated by a new majority shreded the retirement rights of the legislators it replaced. Per Ca. law, the replaced legislators had a vested contract right created by statute. It was a simple case, just like Kern and Allen, but had nothing to do with a Charter City granting a modifiable pension right. In Ca. the law of vested rights is subject to the plenary power granted by the Ca. Constitution to Charter cities. State employee cases are an entirely different class and not applicable to Charter cities.

Why didn’t San Jose pursue its appeal; a new council favored the staff and unions. That council just abandoned the appeal and granted the police unions a 15% raise. Sorry about typos.

November 10, 2015 at 8:10 pm

California cities are on a course of destruction. Pension cost and the raiding of the citiy’s funds by the state are leaving without the ability to provide services. It is insane for these pension contracts of 2.7% or even 3% times high year of income times years of service. The Federal governemnt got out of a 2% plan of high 3 year average back in the early 80’s, but cities in Calif are still stuck thanks to liberal courts of Calif. NV here I come.

November 11, 2015 at 3:05 am

Jerry,

Very accurate comments, but I suggest you pick another State, as Nevada is in AT LEAST as bad shape (due to IT’S grossly excessive Public Sector Pensions & Benefits) as CA.

November 12, 2015 at 9:50 pm

During a time of increased violence and social unrest, undermining the earned compensation and retirement benefits of Public Safety personnel will inevitably result in reduced motivation and dedication of those personnel. The unraveling of negotiated contracts by the various levels of elected government, amounts to a :”you can’t trust

the lawmakers opinion” which can only reduce the historical commitment of the Public Safety personnel who are expected to enforce those laws.

November 13, 2015 at 4:59 pm

Carm J. Grande Says,

One could easily replace “Public Safety personnel” in your above comment with “air traffic controllers”.

They also thought they were untouchable, and back in the 80’s President Regan showed them that they were not …. by firing all of them (permanently). The same should be done with Safety Workers who have a oversize opinion of their worth.

November 15, 2015 at 12:05 am

For Tough Love: I can imagine your opinion will change when an attack occurs in the U.S.A., similar to the event in Paris.

November 16, 2015 at 12:36 am

Like most in NJ, I live in a reasonably nice “bedroom community” where violent crime is near non-existent, and police officers spend their time with traffic stops, medical calls from the elderly, and the occasional mischief from our younger male residents.

And for THIS, they are paid (for a patrolman with only 5 years of service) over $125K in BASE PAY (YUP, that’s true) and a total compensation package (pay plus pensions plus benefits) worth over $200K annually.

How patently absurd.